Wall Type Explanations

This page provides detailed explanations for each type of concrete wall used in this application, including key parameters and design considerations based on the data models.

1. Cast-in-Place

Standard structural wall poured on-site into removable forms.

Key Parameters:

- Concrete Strength (PSI): The compressive strength of the concrete mix, critical for load-bearing capacity.

- Vertical & Horizontal Rebar: The size and spacing of the steel reinforcement bars (rebar) that provide tensile strength.

- Formwork Type: The material and system used to create the mold for the concrete (e.g., wood, steel, aluminum). Affects cost, finish, and reusability.

- Cure Time (Days): The duration required for the concrete to achieve its specified strength.

- Rebar Cover: The minimum distance between the rebar and the outer surface of the concrete, crucial for protecting the steel from corrosion.

Common Uses:

Foundations, basements, shear walls, core walls in high-rise buildings, and retaining walls.

Advantages:

- High strength and durability.

- Monolithic structure with fewer joints.

- Adaptable to complex architectural shapes.

Things to Consider:

- Construction is weather-dependent.

- Requires extensive on-site labor for formwork.

- Longer construction schedule compared to precast.

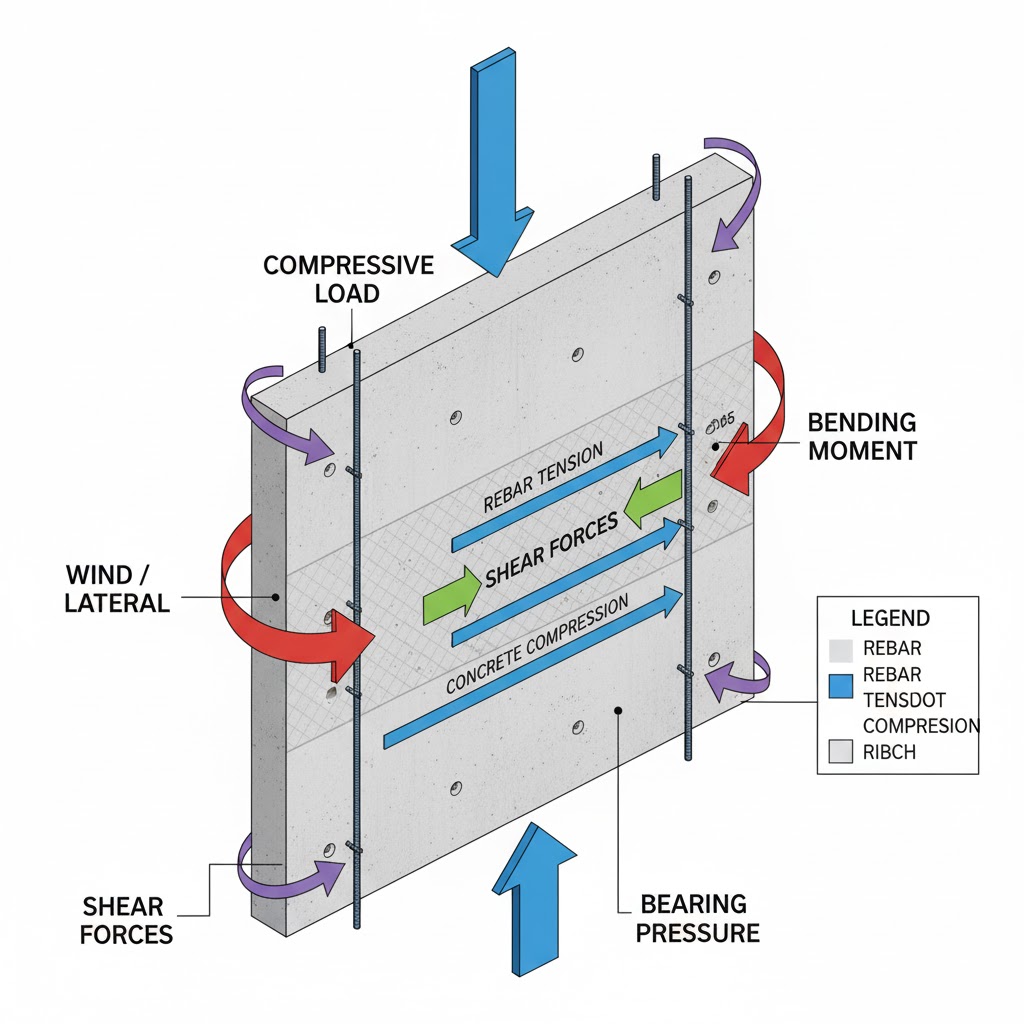

Forces & Verifications:

Forces at Work

Primarily designed for compressive loads (vertical forces). The steel rebar is crucial for handling tensile forces (stretching) from bending or lateral loads (wind, soil) that concrete is weak against.

Key Verifications

- Slump Test: Measures the consistency of fresh concrete before pouring.

- Compressive Strength Test: Concrete cylinders are tested at 7 and 28 days to ensure they meet the specified PSI.

- Rebar Inspection: Verify correct size, spacing, and cover before pouring.

2. Precast

Wall manufactured in a controlled environment off-site and transported to be assembled.

Key Parameters:

- Panel ID & Manufacturer: Identifies each unique panel and its origin for tracking and quality control.

- Finish Type: The aesthetic surface of the panel (e.g., smooth, exposed aggregate).

- Design Weight: Critical for transportation logistics and crane selection.

- Embed Plates & Lifting Inserts: Pre-installed hardware for connections and for lifting panels into place.

Common Uses:

Exterior and interior walls for commercial buildings (offices, warehouses), sound walls, and data centers.

Advantages:

- High-quality control from factory production.

- Fast on-site erection, reducing construction time.

- Not dependent on weather conditions.

Things to Consider:

- Transportation costs can be high.

- Requires heavy lifting equipment (cranes).

- Connections between panels are critical and must be designed and executed perfectly.

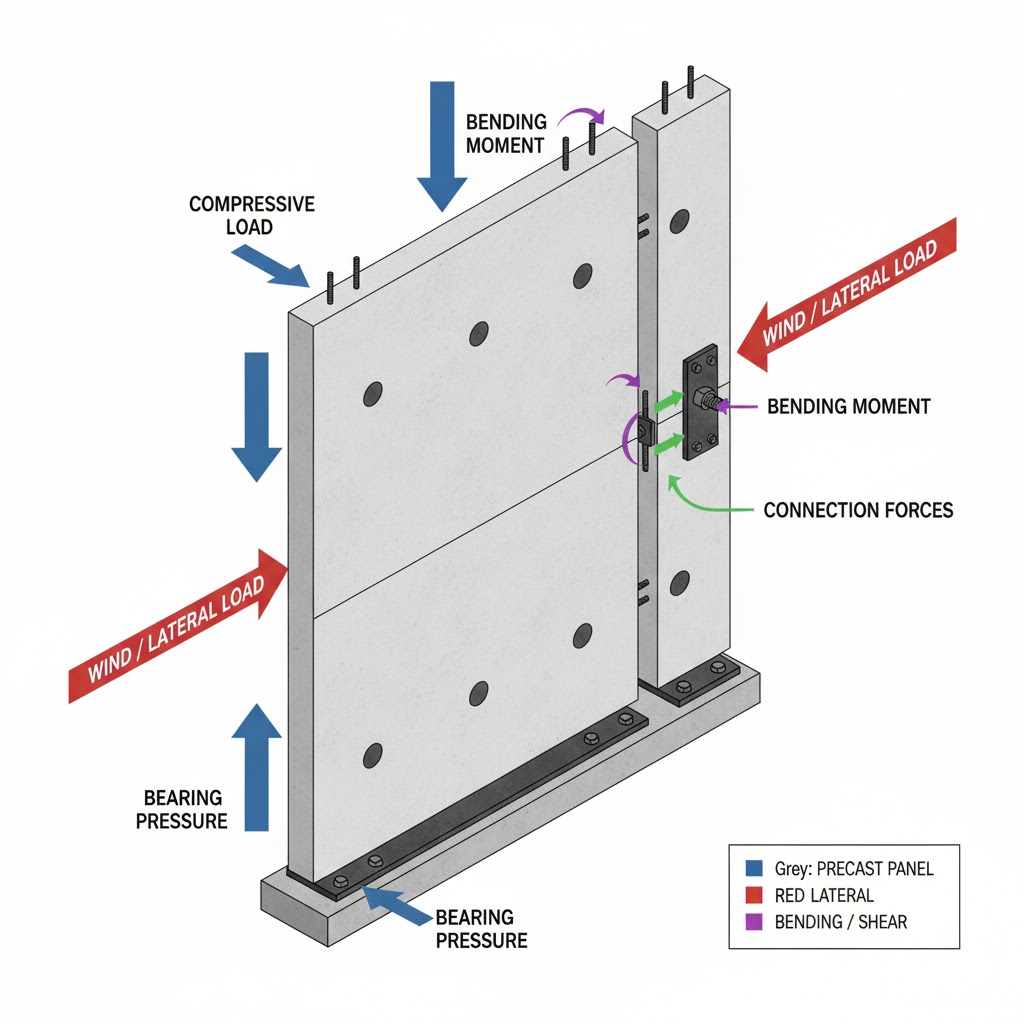

Forces & Verifications:

Forces at Work

Panels handle compressive loads and resist lateral loads (wind). The connections (welded plates, bolts) are designed to transfer these loads between panels and to the foundation.

Key Verifications

- Factory Inspection: QC checks on dimensions, finish, and reinforcement.

- Connection Inspection: On-site verification that all connections are properly welded or bolted.

- Lifting & Bracing Plan: Ensure the plan for lifting and temporarily bracing panels is followed.

3. ICF (Insulated Concrete Form)

A system of interlocking foam blocks that serve as permanent formwork for a concrete core, providing high insulation.

Key Parameters:

- Insulation Material & R-Value: The type of foam and itsthermal resistance, a primary benefit of ICFs.

- Concrete Core & Insulation Thickness: The dimensions of the structural concrete center and the insulating foam layers.

- Web Material: The ties (plastic or metal) that connect the foam faces and hold rebar.

Common Uses:

Residential and commercial buildings, especially where high energy efficiency is desired. Basements and full-height walls.

Advantages:

- Excellent insulation (high R-value), leading to energy savings.

- High sound absorption.

- Fast and easy assembly of forms.

Things to Consider:

- Higher initial material cost than traditional wood framing.

- Requires experienced labor to avoid blowouts during concrete pour.

- Modifications after the pour are difficult.

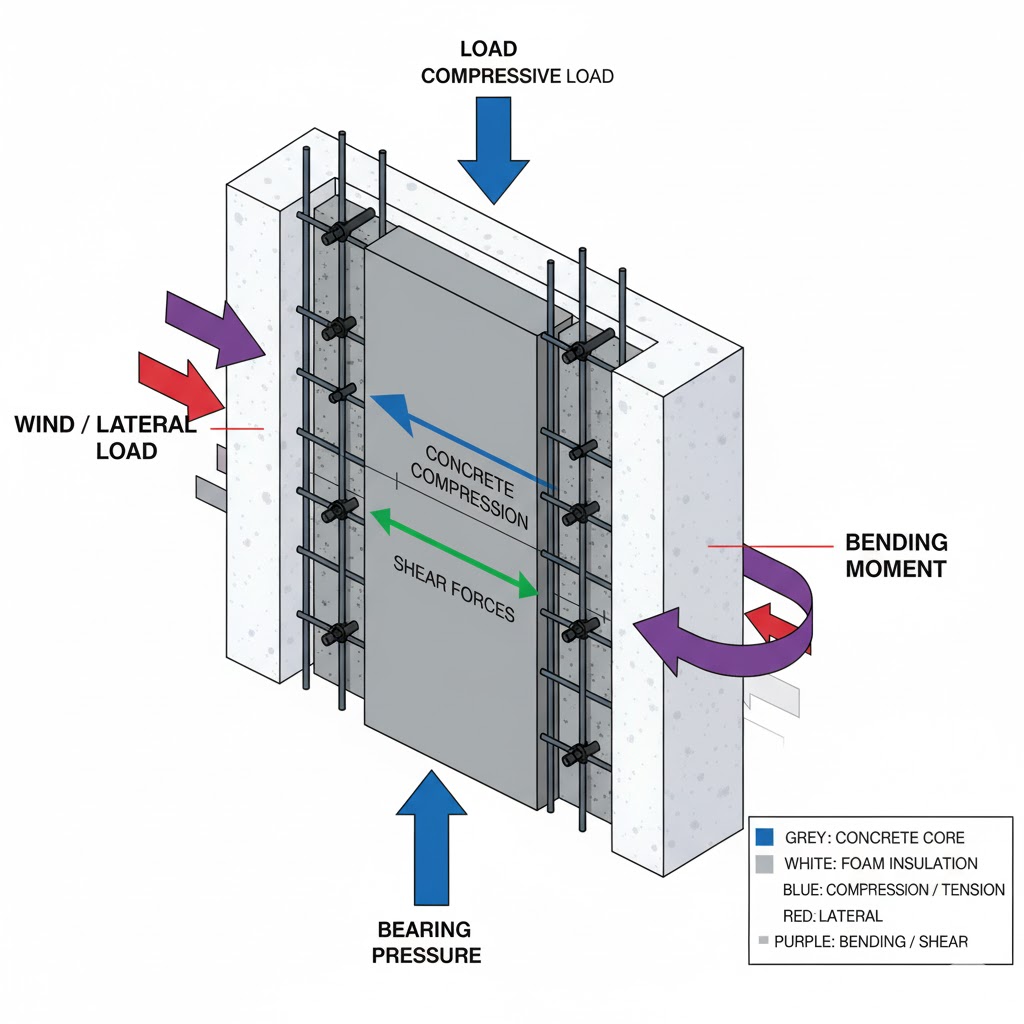

Forces & Verifications:

Forces at Work

The internal concrete core acts as a standard cast-in-place wall, handling compressive and lateral loads. The foam provides no structural strength but protects the concrete and provides a substrate for finishes.

Key Verifications

- Form Assembly Check: Ensure blocks are properly interlocked, braced, and aligned before the pour.

- Concrete Consolidation: Proper vibration is needed to ensure no voids (honeycombing) form within the core.

- Waterproofing: Below-grade applications require careful waterproofing over the foam exterior.

4. Tilt-Up

Wall cast horizontally on the building's floor slab or a temporary casting bed on-site and then tilted vertically into place.

Key Parameters:

- Panel Name: Identifier for the specific wall panel.

- Lifting Insert Type: Engineered hardware to handle the stresses of lifting the panel.

- Bracing Details: Temporary supports that hold panels until the roof structure is tied in.

- Casting Slab Thickness: The slab must be sufficient to support the panel casting load.

Common Uses:

Large commercial buildings, such as warehouses, distribution centers, and retail stores.

Advantages:

- Cost-effective for large, simple buildings.

- Fast construction schedule.

- Durable and low-maintenance.

Things to Consider:

- Requires a large, open site for casting panels.

- Lifting day is a critical, high-risk operation requiring a large crane.

- Limited to relatively simple, flat panel shapes.

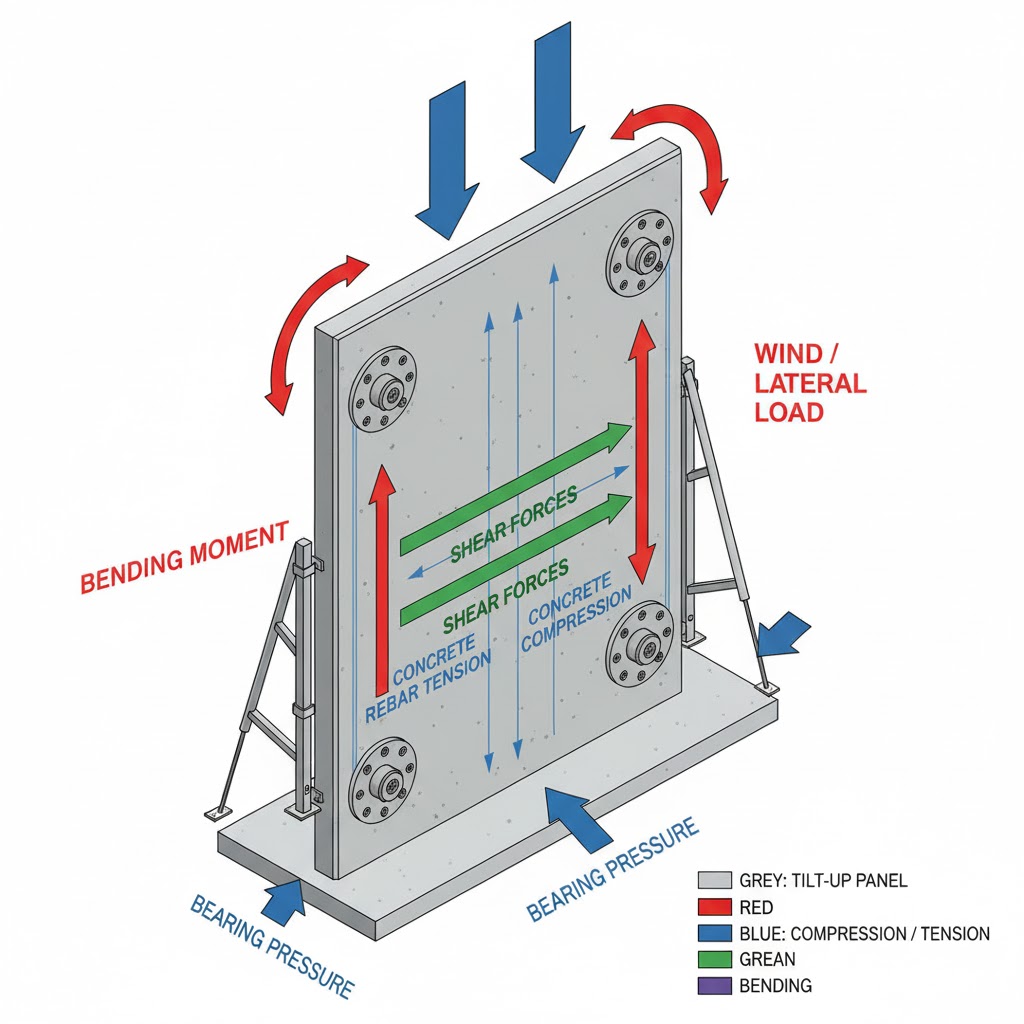

Forces & Verifications:

Forces at Work

The most critical forces are the bending stresses during the lifting process. Once vertical, they act like precast panels, handling compressive and lateral loads. The temporary bracing is crucial for resisting wind loads before the roof is installed.

Key Verifications

- Lifting & Bracing Plan Review: A licensed engineer must design and approve the plan.

- Insert Placement Check: Verify the location of lifting inserts before pouring concrete.

- Concrete Strength: The concrete must reach a specified minimum strength before the panels can be lifted.

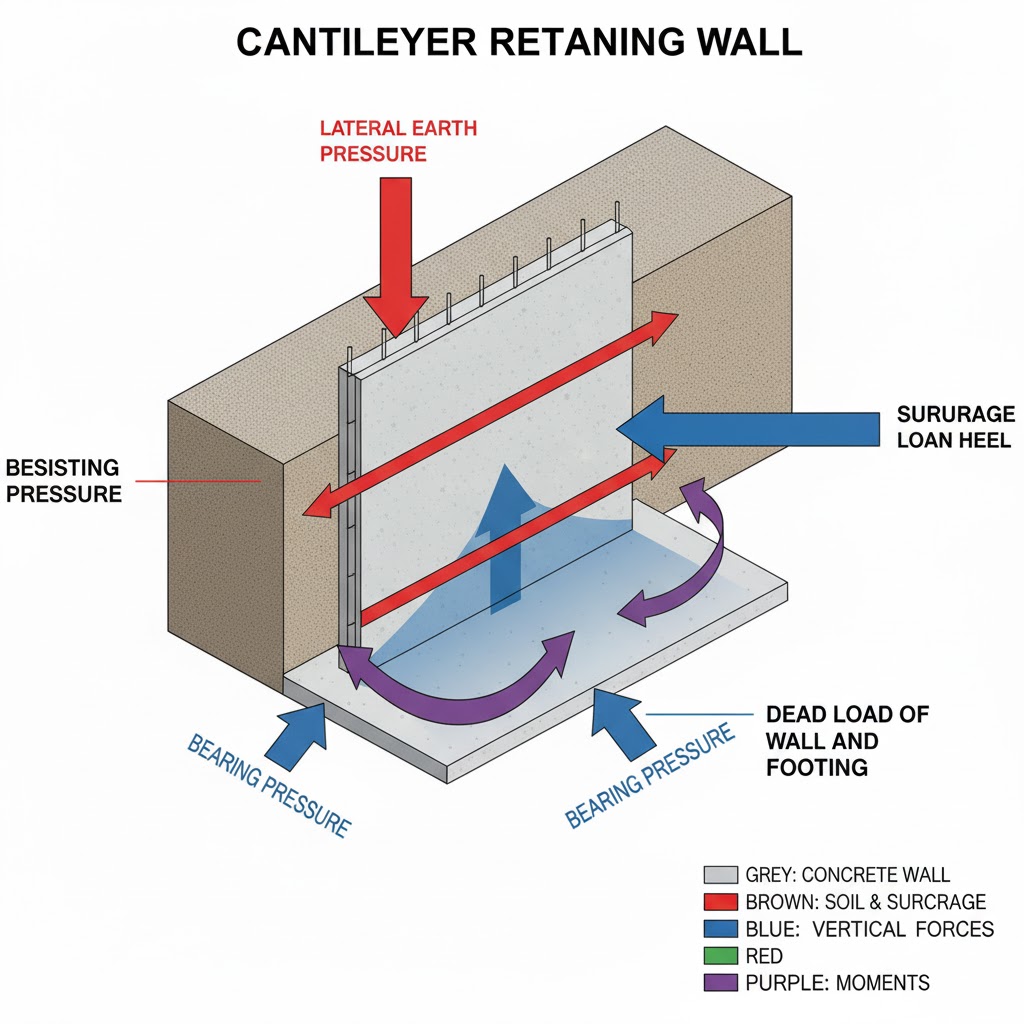

5. Retaining

Wall designed to hold back (retain) earth or other materials, resisting lateral pressure.

Key Parameters:

- Retaining Type: The structural design (e.g., Gravity, Cantilever, Anchored).

- Soil Pressure: The expected lateral force from the soil.

- Heel & Toe Length: The footing dimensions that provide stability against overturning.

- Key Depth: A projection below the footing that increases resistance to sliding.

- Surcharge Load: Additional load on the soil behind the wall (e.g., from a driveway).

Common Uses:

Creating level terraces on sloped land, basement walls, and supporting roadways and bridges.

Advantages:

- Enables development on sloped terrain.

- Prevents soil erosion.

- Can be designed with a wide variety of materials and finishes.

Things to Consider:

- Proper drainage behind the wall is absolutely critical to prevent failure.

- Requires a geotechnical report to understand soil properties.

- Design is complex and must account for multiple failure modes.

Forces & Verifications:

Forces at Work

The primary force is the lateral pressure from the soil, which creates an overturning moment (wants to tip the wall over) and a sliding force (wants to push the wall forward). The wall's own weight and the weight of the soil on its heel create a resisting moment and frictional resistance to counteract these forces.

Key Verifications

- Safety Factor (Overturning): The resisting moment must be significantly larger than the overturning moment (typically > 1.5-2.0).

- Safety Factor (Sliding): The frictional resistance must be significantly larger than the sliding force (typically > 1.5).

- Bearing Pressure: Ensure the soil underneath the footing can support the total load without settling.

6. Retaining - Sheet Pile

Flexible wall system driven into the ground, deriving stability from the soil resistance below the excavation line (Cantilever action).

Key Parameters (WisDOT 14.5):

- Embedment Depth (D): The calculated depth required below the "dredge line" to prevent the wall from tipping over.

- Friction Angle (φ): The internal soil strength parameter determines Active and Passive earth pressure coefficients.

- Section Modulus (S): The structural property of the pile (steel or concrete) required to resist the Maximum Moment.

- Water Table Elevation: The level of groundwater, which creates hydrostatic pressure on the wall.

Common Uses:

Waterfront structures (bulkheads), floodwalls, temporary shoring for excavations, and cofferdams.

Advantages:

- No Footing Required: Does not require excavation for a base slab; driven directly into the ground.

- Speed: Very fast installation using vibration or impact hammers.

- Watertightness: Interlocking joints can cut off groundwater flow.

Things to Consider:

- Height Limits: Cantilever walls are typically limited to heights of 15ft (4.5m) before requiring anchors (tiebacks).

- Installation Vibration: Driving piles can damage nearby structures.

- Corrosion: Steel sections may require coating or sacrificial thickness for long-term durability.

Forces & Verifications:

Forces at Work

The wall acts as a vertical cantilever beam. The soil above the excavation line exerts Active Pressure (pushing out). The soil below the excavation line provides Passive Pressure (pushing back). The wall rotates around a pivot point near the bottom.

Key Verifications

- Rotational Stability: Sum of Resisting Moments (Passive) must exceed Driving Moments (Active) by a Safety Factor.

- Maximum Moment (Mmax): The wall section must be strong enough to resist the bending force at the point of Zero Shear.

- Deflection: The top of the wall must not bow out excessively.

ConcreteWalls2

ConcreteWalls2 v1.0.0

Copyright Ⓒ 2025